CaSH - A Simple Shell

During the spring, I read the book Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau and Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau. Having read the book, I wanted to learn more about systems programming through a project of some sort, so I decided to try and write my own shell with my own grammar and a couple of extra functionalities. Here’s a short write-up about the project (github link).

The Overview

I wanted to create a short grammar for the shell, with options to pipe other commands in sequence, to redirect output to files and to read input from other files. I also wanted to include environment variables, so that you could set for example API keys and other secrets in the shell. I created simple data structures for a simple_command, which is a command with zero or more arguments, as well as for a command, which is basically an array of one or more simple_commands. These data structures then contain the logic of actually executing the commands by forking child processes from the parent process.

In the dirsum command, CaSH basically crawls through your directory, avoids hidden files starting with ".", takes the first 2000 bytes from each file, packs them into a JSON array using cJSON, sends them as an HTTP request and then streams the response using SSE.

Btw don't worry, I deleted the API key I used in the video!

However, before that could be done, the shell needed a grammar. Apart from the command data structures, the grammar required two parts: a lexer and a parser.

Lex/Flex

Lex is a so-called scanner generator. Its input is a set of regular expressions and associated actions that are written in C. It outputs a table-driven scanner in a file lex.yy.c Lex is a standard Unix tool developed in the 70s, but for example macOS ships nowadays with Flex, which is a more efficient open-source version.

Basically you have to define tokenization rules of the form

%{

/* You can place your basic include statements here */

#include <string.h>

%}

%%

/* Here you specify the pattern with regular expressions that has to match, along with a C code block to be executed */

"|" {

return PIPE;

}

%%

/* At the end you can specify C code, for example functions that you use in the section above */

The rules you can implement with Flex are limited to those you can express with regular expressions, called regular languages. This is why in order to develop a complex syntax for a shell or a programming language, you most often need a parser as well. For the syntax of CaSH we need a parser that can handle context-free grammar

Yacc/Bison

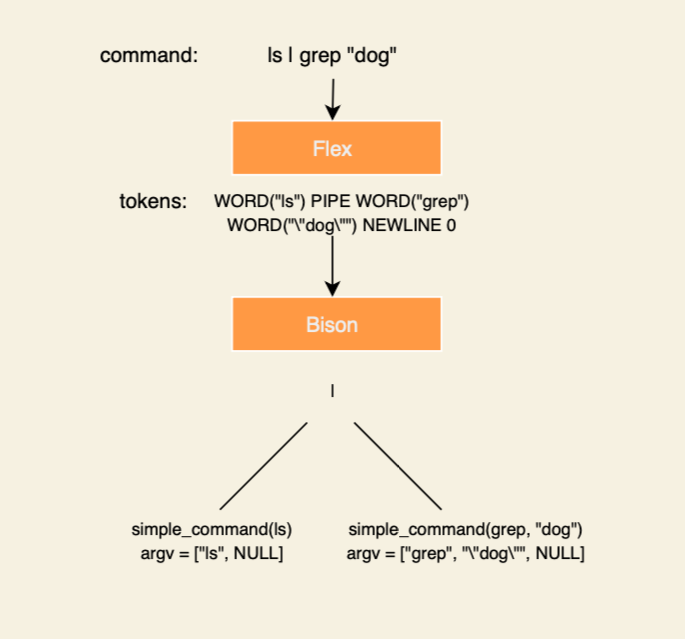

Yacc (Yet Another Compiler-Compiler) is a parser generator that generates, as you might guess, a parser. This parses parses the stream of tokens generated by the lexer and lets us do semantic processing based on that. Once again, the version that you’ll encounter on most systems is not Yacc, but rather Bison, which is GNU’s open-source replacement that also has other capabilities. By the way, if you didn’t happen to know, GNU has a recursive acronym in its name (GNU’s Not Unix), which is nice. The figure below demonstrates the roles of the lexer and the parser.

Bison is a LALR parser generator, which means that it reads a context-free grammar and creates an LALR parser. A LALR parser is a look-ahead, left-to-right, rightmost derivation parser. To be more specific, Bison generates LALR(1) parsers by default, which means that the LALR parser has a one-token lookahead, which, in turn, just means that the parser looks only at the next token to make a decision at the current step.

A LALR parser works by maintaining a stack of (state, semantic-value) pairs. It parses the stream of tokens that the lexer generates from left to right. When it pushes a token to the stack, it checks whether it can reduce one or multiple tokens to some nonterminal symbol. If it can reduce symbols, it pops them from the stack, executes the code specified in the grammar and pushes the new nonterminal symbol onto the stack, otherwise it shifts to the next token.

Take for example this context-free grammar

%{

#include <stdio.h>

%}

/* All the named tokens must be declared to the parsers. This is how it knows for sure that

these tokens cannot be reduced further. Single-character literals, like '+' can be used without a %token declaration */

%token NUM '+'

%token NEWLINE

%%

stmt

/* This means that an expression followed by a newline on the stack can be turned into a statement, and at the same time

we print the value of the expression */

: expr NEWLINE { printf("= %d\n", $1); }

;

expr

/* This means that a NUM can be converted to expr, and when we do this,

we should also assign the value of the first argument (in this case NUM) to the value of the LHS (in this case expr) */

: NUM { $$ = $1; }

/* This means that if we have {expr, '+', NUM} on the stack,

we should reduce it to be {expr} and assign the expr to have the value of the previous expr + NUM */

| expr '+' NUM { $$ = $1 + $3; }

;

%%

Now take this stream of tokens as an example:

NUM(3), '+', NUM(4), '+', NUM(5), NEWLINE, EOF

This is how it gets processed by the LALR parser:

| Step | Stack Before | Lookahead | Action | Stack After |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | empty | 3 |

Shift 3 |

3 |

| 1 | 3 |

+ |

Reduce expr → NUM (base case) |

expr(3) |

| 2 | expr(3) |

+ |

Shift + |

expr(3) + |

| 3 | expr(3) + |

4 |

Shift 4 |

expr(3) + 4 |

| 4 | expr(3) + 4 |

+ |

Reduce expr → expr '+' NUM (“3+4”) |

expr(7) |

| 5 | expr(7) |

+ |

Shift + |

expr(7) + |

| 6 | expr(7) + |

5 |

Shift 5 |

expr(7) + 5 |

| 7 | expr(7) + 5 |

↵ |

Reduce expr → expr '+' NUM (“7+5”) |

expr(12) |

| 8 | expr(12) |

↵ |

Shift ↵ |

expr(12) ↵ |

| 9 | expr(12) ↵ |

EOF |

Reduce stmt → expr NEWLINE (print “=12”) |

stmt |

| 10 | stmt |

EOF |

Accept | done |

Commands

Having specified the necessary grammar in the shell.l and shell.y files, I then implemented some of the built-in commands that modify the state of the shell, like cd, export, unset, exit and so on. These largely relied on the POSIX APIs and the C standard library. For the input redirection I basically created an array of pipes using pipe() and then used dup2() to wire stdin/stdout to the correct ends of each pipe.

I also implemented support for environment variables. The shell.l regular grammar needed some reworking to support variable references. It also supports environment variable expansion, so if you have previously executed

export NAME=john

then $NAME expands to john.

The dirsum command needs a special mention. I thought it’d be nice if you could just instantly get a summary of the directory you are in currently. Basically the shell crawls the directory using POSIX system calls, following the typical opendir(), readdir(), lstat() pattern, skipping files that start with “.”. It takes the first 2000 bytes of each file and wraps it into a JSON object of the form {“path”, “size_bytes”, “head”} using cJSON. Then it sends a POST request to the OpenAI API with an easy_curl connection, and in the write callback it implements an SSE parser.

SSE messages are sent in events, where a single complete message from the API may be split up into multiple events, so the callback function had to buffer the events into lines and then into complete blocks. From each block, it extracts the last “data:” line and parses it as JSON.

I also tried out the Catch2 C++ testing framework and wrote a couple of unit tests for the command data structures and an integration test for the piping feature.